Coordinated Response

Services and tools for incident response management

Security Failures

Ubiquitous Limitations with Incident Response

A data forensic expert, often involved with response to a cybersecurity incident, identified 9 limitations he repeatedly experiences with organizations when he participates in their incident response.

These 9 weaknesses or limitations hinder incident response efforts – costing time, money, and potentially the organization’s reputation.

Addressing the 9 limitations makes a good set of New Year’s resolutions. These resolutions form the outline of a good plan for incremental improvements throughout the year to come.

The table below addresses these limitations in the form of an incremental plan. It’s divided into 3 phases: Phase I – Lay a foundation; execute tasks that would result in time savings if an incident occurs; Phase II – Pluck low hanging fruit; execute tasks that would immediately improve your security profile and reduce the likelihood of an incident; and Phase III – Plan and raise your security profile; add procedures and tools to enhance your cybersecurity incident response capabilities.

| Phase I | Phase II | Phase III |

|---|---|---|

| Inventory and Inventory Control | Legacy Equipment and Software – Low Hanging Fruit | Legacy Equipment and Software – Incremental Reduction |

Review or Develop the Inventory of IT Assets:

|

Through the inventory process identify low hanging fruit – remove components that can be retired or replaced easily. Develop a plan to remove remaining items through a phased approach. Include a budget and a return on the necessary investment. Tie investment to risk reduction and value to the organization. | Implement a cost / benefit approach to incrementally eliminate legacy components. Include remaining legacy components in a risk register; plan to address these components next year. |

| Change Control | Harden DMZs | Network Visibility |

| Along with inventory control, establish and follow policies and procedures that control changes to the IT infrastructure. Limit end users’ ability to install software. Limit the ability to modify hardware and software configurations. Audit changes. |

Too often, DMZs look good on paper, but have been degraded with time. As a result of the inventory process, review the DMZ, close gaps, harden it, and update the documentation. |

Improve the network inventory – know the scope of the network and its components. Improve network monitoring tools. |

| Administrative Accounts | Staff Capabilities and Requirements | Incident Response Capabilities |

| Identify and limit administrative accounts. Employ least privilege and separation of privilege. | Review staff capabilities and requirements. Develop plan to fill gaps through hiring, training, realigning. | Review the risk assessment and incident response plan. Identify gaps and a plan to fill them. |

| Users – Policy | Users – Education and Training | Users – Monitoring |

| Review / establish policies including acceptable use of IT assets and privacy. Address mobile devices especially “bring your own devices” (BYOD). | Educate users on the policies; establish their acceptance of the policies. Develop and implement awareness training. | Establish tools to monitor users especially users with elevated privilege. |

A Coordinated Response to Cybersecurity

Phase I might include an incident response plan review. The response plan includes input from the following activities: inventory, privilege accounts, and staffing requirements. It provides input to the staffing requirements, legacy equipment, and incident response capabilities. So, if you resolve to improve your cybersecurity posture in the coming year, Coordinated Response can help you get started with a response plan review.

GAO Statistics for Cybersecurity Incidents

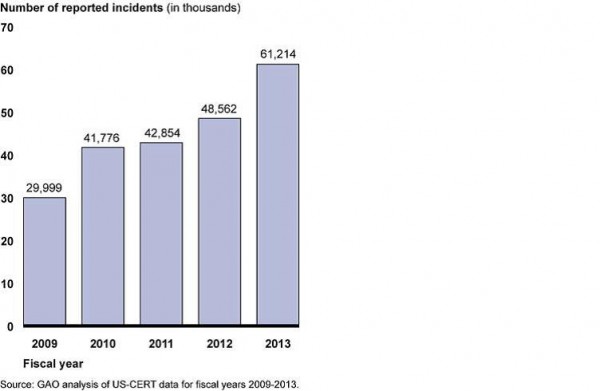

Cybersecurity incidents double in 5 years

In a report of recent congressional testimony, GAO provides statistics that provide insight. The report is available from the GAO Web Site.

Incidents over Time

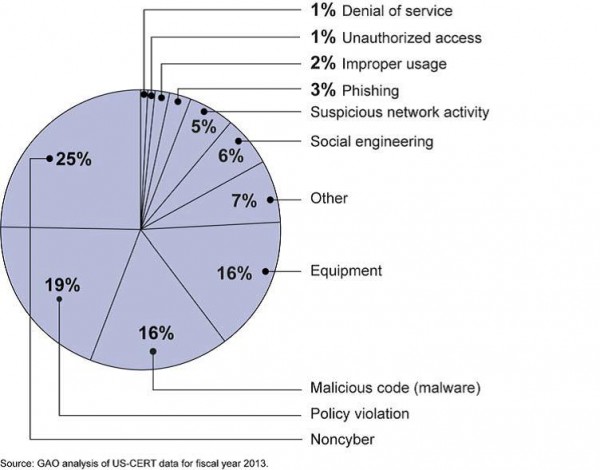

Incidents by Category

Coordinated Response

How does this compare with your experience? Does your response plan address this range of cybersecurity incidents? At Coordinated Response we use this type of information to inform our response plan development and response plan reviews.

Department of Energy Hack Raises Issues

The Washington Free Beacon reported on 2/4/2013, “Computer networks at the Energy Department were attacked by sophisticated hackers in a major cyber incident two weeks ago and personal information on several hundred employees was compromised by the intruders”. A total of 14 computer servers and 20 workstations at the headquarters were penetrated during the attack.

This article and other articles in the recent past all raise the same issue: inadequate security measures stemming from (pick one or more): improperly trained administrators, inexperienced security staff, budgetary constraints, and/or “institutional hubris”. Government has a responsibility to protect the information entrusted to it by its citizens. However, the government – all branches – has failed in this endeavor and will likely continue to fail until they wake up to reality and get smarter than those attempting to compromise their systems.

Mandatory security testing and training must be implemented at all levels of IT and operations throughout the government. If sensitive information is involved, training must be held. I am not talking about awareness training; I am talking about training the administrators, IT managers and security staff on what to look for, how to properly program and configure and, most importantly, how to test systems and how to properly conduct attack and penetration tests.

Do not rely on hiring people with long strings of certifications behind their names. In many cases, they are merely cert collectors who have no clue as to what the certs really mean – other than the more certs you have the better chances of getting a job. Establish real training programs. Work with groups such as the GIAC (Global Information Assurance Credentials) which has programs that REQUIRE a practical exercise before a cert can be awarded. NSA relies on GIAC certified individuals, why shouldn’t the rest of government?

Finally, forget sending trained staff away to conferences. Not only will the conferences be a waste of time – it seems only controversial, contrarian views are desired for talk topics these days – but you will leave your networks and systems in the hands of those not as qualified to deal with crises should the inevitable happen. Everyone likes to go to conferences (if for no other reason than to collect suitcases full of vendor-supplied swag) but the best bet on training spending is on real training as supplied by organizations such as the SANS Institute.

CSO magazine analyzing this story provided a number of sources that support the same conclusion.

New York Times Hacked Again

The New York Times incident response and incident handling provides examples of best practices, as well as, lessons learned.

According to the New York Times, Hackers in China Attacked the Times for Four Months. The Times Incident Response Plan provides examples of best practices as well as lessons learned.

|

|

And the most important best practice is to make security improvements based on the postmortem and lessons learned

In the case of the New York Times, the hackers were able to crack the password for every Times employee. Then the hackers used the passwords to gain access to the personal computers of 53 employees. The attack was discovered on October 25. The investigation placed the initial compromise on or around September 13 or 6 weeks earlier.

First, the Times engaged their Internet Service Provider (ISP), AT&T, to watch for unusual activity as part of AT&T’s intrusion detection protocol. The Times received an alert from AT&T that coincided with the publication of a story on the Chinese Prime Minister’s family wealth.

The New York Times briefed the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). The FBI has jurisdiction over cybercrimes in the United States.

At the start of week 9, when the response team, even with AT&T assistance, was unable to eliminate the malicious code, the Times engaged Mandiant, a firm specializing in cybersecurity breaches. This is both a lesson learned and a best practice. Expect to need additional help when a significant incident occurs, but it’s best to engage the specialists when the response plan is first developed.

The response team identified 45 pieces of malware that provided the intruders with an extensive tool set to extract information. Virus protection only identified 1 piece. This is an important lesson. Advanced or enhanced malware may be difficult to detect. Defense in depth requires added security controls. In this case, monitoring provided the alert.

At this point, the response team “allowed hackers to spin a digital web for four months to identify every digital back door the hackers used”. This allowed the Times to (1) fully eradicate the intruders, (2) determine the extent of the intrusion and data extraction, and (3) build improved defenses for the future. Again, this is a best practice – investigation precedes eradication.

I found the work habits of the hackers particularly interesting. They worked a standard day starting at 8 A.M. Beijing time. Occasionally they worked as late as mid-night including November 6, election night.

Five Failures

I recently read an article on Computerworld.com titled Unseen Cyber War that, in my mind, was more about spreading fear, uncertainty and doubt (FUD) than it was about objective reporting. The focus should have been more about solving problems rather than wringing of hands, gnashing of teeth and creating unreasonable angst and concern about vulnerabilities that should have been fixed or at a minimum, mitigated.

While the threats are real, this type of FUD does not help. The real problem is fivefold:

1. Failure to deliver secure products by hardware and software vendors. Software riddled with bugs and poor programming techniques and hardware configured in ‘open’ modes are recipes for disaster.

2. Failure to enforce security standards by IT departments on devices facing the Internet and to securely configure routers, servers and other networking and computing devices. Putting devices in service and connecting them to the Internet without changing default settings is insane.

3. Failure to properly allocate resources by executive management in government and private industry to train users on secure computing practices. CISOs are ready to train users, but until CIOs and CEOs understand the full ramifications of ignorant user-bases, problems such as phishing/spear phishing, drive-by malware and similar attacks will continue.

4. Failure of our education system to teach proper security techniques to students at all levels of the education ladder. Many children today are familiar with computers and tablets by the time they enter first grade. Teachers should prepare syllabi aimed at appropriate grade levels that teach both security and ethics. Until this training is institutionalized throughout the education life-cycle (primary, secondary and university levels) there will be problems.

5. Failure by parents to understand what their children are doing on the Internet. Being open and honest with children is the best way to make sure children and young adults listen to you. Make sure you let them know that accessing the Internet by any device — mobile or otherwise — is a privilege not a right. Parents should monitor use and let their kids know they are doing it. Don’t be sneaky about it; installing silent “net-nanny” software without telling the progeny that it’s there will just raises trust issues and the kids will just figure a way around it.

Fix these five elements and you will have less problems with hackers, crackers and other ne’er-do-wells.