Coordinated Response

Services and tools for incident response management

Best Practices

6 Key Ingredients to a Law Firm Data Security Plan

Jeff Norris, Senior Director of IT Security for Lexis/Nexis Managed Technology Services identified 6 Key Ingredients to a Law Firm Data Security Plan on the Lexis/Nexis Business of Law web site (May 2015). An incident response plan was one of those ingredients.

Data Security Key Ingredients

The following ingredients really apply to any organization evaluating their data security posture, not just law firms.

- Clear Policy and Training Plan.

- Accurate Inventory.

- Access Controls.

- Keep Software Updated.

- Review Liability Coverage.

- Plan for Incident Response.

The first 4 ingredients are about Protect – protecting your data. The last 2 ingredients are about Respond – responding to a cybersecurity incident. This is a clear recognition of the likelihood of an incident.

Coordinated Response

Let us help your organization develop, improve, and test your incident response capabilities.

The full article by Daryn Teague (May 2015) is available at this link:

http://businessoflawblog.com/2015/05/law-firm-data-security/

Cyber Incident Response – Executive Awareness

Raising executive awareness on the importance of incident response planning should raise executive support. This is one in a series of references that serve as tools for engaging your executives and gaining their support.

The full collection of references is available at this link:

https://coordinatedresponse.com/topics/incident-response-plan/executive-awareness//

Penn State and a Coordinated Response

Penn State was hacked, but returned “a coordinated and deliberate response.”

NOTE: Our firm, Coordinated Response was NOT involved, but we can all learn from Penn State’s response. The response includes a number of best practices highlighted in this article.

On May 15, 2015 Penn State announced the discovery of two sophisticated cyber attacks. “In a coordinated and deliberate response by Penn State, the College of Engineering’s computer network has been disconnected from the Internet and a large-scale operation to securely recover all systems is underway.”

For more details read the announcement on the Penn State web site, but here are some best practices.

An Effective Communications Plan

Penn State announced the breach on May 15. On the same day, they released the web site http://securepennstate.psu.edu/ to keep students and faculty informed of events. The URL suggests they were prepared for any eventuality. Penn State also notified research partners and individuals who may have had sensitive data exposed to the intruder.

Detect and Analyze

On November 21, 2014, the FBI alerted Penn State of a cyber attack with unknown origins and scope. The University’s security experts along with outside experts began an extensive investigation. Mandiant, a FireEye company, was one of the experts. The investigation determined that the earliest confirmed date of intrusion was September 2012 — over 2 years earlier.

Contain: Protect and Preserve

Steps were immediately taken to further protect and preserve critical information and sensitive data on the College of Engineering Systems.

Cone of Silence

No announcements were made to avoid alerting the intruder and to avoid unwanted damage or destruction.

Eradicate and Recover

On May 15, once the scope and nature of the intrusion were known, the engineering systems were taken offline to remove malware, secure the systems, and restore them to operational status. This is expected to take several days. All passwords are being reset to address potentially compromised credentials.

Communicate

Once the investigation was completed the communication plan was launched.

Lessons Learned

Two factor authentication for remote access to the Engineering systems is being implemented now. This will be extended to the rest of the University later this year. Additional measures were taken to improve the security posture.

Coordinated Response

One might question why it took over 2 years and an outside organization to discover the intrusion. But, experience suggests state actors operate “slow and low”. First, the intruders observe without leaving “foot prints” for an extended period. Then, instead of leaving 10 foot prints a day, they leave 1 a day for 10 days. They work hard to make it hard to detect.

But, once alerted, Penn State responded with a well planned and well coordinated response. Let us help your organization with an incident response plan review. Together, we can apply best practices to improve the plan and the outcome of a cyber incident.

FIRST Recommended Incident Categories

Categorizing incidents helps establish a consistent and effective Incident Response Plan.

FIRST, the Forum for Incident Response and Security Teams, provides great resources for developing an Incident Response Plan through the FIRST Web Site.

One web page provides guidance on Incident Categories that we use as a baseline for the initial categories in our Response Management Framework. The guidance stresses Consistent Case Classification/Categorization to help achieve key objectives:

- Provide accurate reporting to management;

- Insure proper case handling; and

- Form the basis for Service Level Agreements (SLAs) between the CSIRT and other departments.

Consistent Categories also address the following:

- Effectively communicate the scope of CSIRT responsibility to executives and constituents;

- Inform the development of appropriate response actions; and

- Insure consistent case handling.

Like incidents are likely to require like actions. This helps in the development of the response plan and its effective execution.

Incident Categories

The following table presents the FIRST categories on the left and the categories as adapted for the Coordinated Response Management Framework on the right.

| Categories Proposed by FIRST | Comments / Suggestions |

| Denial of Service – DoS or DDoS attack; attrition. | Every organization experiences DoS at some point. |

| Forensics – any forensic work performed by the CSIRT. | Forensics may be one of many services performed by the CSIRT. CSIRT Services might make a better category with Forensic Services as a specific service type. |

| Compromised Information – attempted or successful destruction, corruption or disclosure of sensitive information. | |

| Compromised Asset – host, network device, application, or user account. | The assets mentioned serve as examples. Mobile devices, any computers: desktop, laptop, notepad, might also be compromised. Lost or stolen equipment might be considered compromised, but perhaps this should be an additional category. |

| Unlawful Activity – theft, fraud, human safety, or child porn. | Any number of incident categories might result in illegal action. Perhaps, unlawful activity might better serve as an impact category. In most cases of unlawful activity, this is not known at the incident response outset. |

| Internal Hacking (inactive or active) – recon or suspicious activity with internal origins. | |

| External Hacking (inactive or active) – recon or suspicious activity with external origins. | |

| Malware – a virus or worm typically affecting multiple corporate devices. | |

| Email – spoofed email, SPAM, etc | |

| Consulting – security consulting unrelated to a specific incident. | This is another example of a CSIRT Service. |

| Policy Violations – inappropriate use, sharing offensive material, or unauthorized access. | As with unlawful activity, policy violation may be a measure of incident impact. |

The FIRST categories have been re-ordered to more readily reflect the mapping to the Coordinated Response proposed categories.

The categories for Compromised Information and Assets are augmented with a category for Loss or Theft of Equipment. These 3 categories share common actions, but there are distinct actions as well. Because each of these categories represent a number of distinct incident types they are best left as separate categories.

DDoS, Email, and External hacking are better treated as incident types and combined under a category for External Incidents. Attacks originating outside an organization are likely to involve a set of external resources from the Internet Service Provider (ISP) to external reporting authorities.

Internal Incidents very likely involve Human Resources and Legal. Internal Hacking is an incident type. Policy Violation may not represent an incident type, but a level of impact.

Unlawful activity is a measure of the legal impact of the incident. External or Internal hacking might rise the level of Unlawful Activity. Or not.

Finally, CSIRT Services might include Forensics, Consulting, and other services. This reflects an important category. The CSIRT might analyze and summarize Threat Intelligence and provide a synopsis to internal audiences.

Impact Levels

The FIRST guidance on categories also introduces Sensitivity and Criticality. Sensitivity applies to the nature of the incident. Denial of Service might rate S3 – Not Sensitive or Low Sensitivity. Policy Violations might rate S2 – Sensitive or Medium Sensitivity. A Forensics Request or Compromised Information might rate S1 – Extremely Sensitive or High Sensitivity. Criticality is measured in a similar way.

The Response Management Framework considers Sensitivity and Criticality as impact areas with associated impact levels. A future highlight on Impact Assessment will include more on FIRST guidance.

Other Categories

Other organizations propose categories for use in incident response planning – organizations including US-CERT at the Department of Homeland Security, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), and the National Institute of Science and Technology.

A future highlight will address incident categories advanced by these organizations and how the proposed categories relate to other categories.

Coordinated Response

Recognizing an incident and its category aligns actions with desired outcomes. Categories need to reflect an organization, its response team, and its security controls. The categories presented here are offered as a starting point and a proven best practice.

Refer to our Response Management Framework for added insight.

Let us help you with a response plan review that considers your information security risk assessment.

US-CERT: Combating Insider Threat

A High-Level View to Help Inform Senior Management

The US-CERT Web Site offers a 5 page paper on “Combating Insider Threat”.

This well written document summarizes the nature of the threat and an approach to detect and deter malicious insider activity. The paper is valuable for 2 reasons:

- It is the right document from the right source to inform executive leadership and board members on the importance of addressing insider threats; and

- It provides a great set of references – good resources for informing an effective program to address insider threat.

First, Consider the Insider

The paper describes the characteristics of “an Insider at Risk of Becoming a Threat” – characteristics recognized by executive leadership. The characteristics of a troubled employee – for example, rebellious or passive / aggressive activity; low tolerance for criticism – may lead to difficulties in a number of ways including a cyber incident.

The paper then identifies “Behavioral Indicators of Malicious Threat Activity” – indicators including an employee interest in areas outside the scope of their responsibility or an employee accessing the network at odd hours or while on vacation or sick leave. Monitoring employee activity is an important part of identifying potential threats.

Then, Detect and Deter

The paper identifies technologies for detection and deterrence. Technologies include data-centric security: data/file encryption, data access control /monitoring, and data loss prevention; intrusion detection / prevention systems; and enterprise identity / access management. The paper helps make the case for the use of the technologies.

The paper also describes the social science behind deterrence strategies – strategies equally applicable to fraud, cybersecurity, and other bad behavior.

Finally, References and Resources

The paper cites 32 references, 29 with online links. I strongly recommend downloading the paper and perusing the links for those that might enhance your insider threat program.

It starts with a link to the Carnegie Mellon CERT Insider Threat web site.

Coordinated Response

This paper focuses on how to Deter and Detect insider threats. We focus on the Coordinated Response to an insider incident. We can help make the case to executive leadership on building an effective insider threat program.

Let us help you with a response plan review that considers your information security risk assessment.

What to Do After a Data Breach

Eight Best Practices to Effectively Deal with a Data Breach

On the CIO Insight web site Karen Frenkel posted a slide deck that identifies 8 best practice for dealing with a data breach. The practices identified align nicely with the elements Response Management Framework.

I recommend the slide deck as a good device for a review and a discussion with your executive team.

Eight Best Practices for a Data Breach Response

- Prepare and Practice to Make Perfect.

- Don’t Panic!

- Move Quickly, but Stay Patient.

- Don’t Go It Alone.

- Assemble the Right Team.

- Get Legal Advice.

- Someone Needs to Talk.

- Identify Lessons Learned.

Coordinated Response

So apply these best practice as you evaluate and improve your incident response plan. Refer to our Response Management Framework for added insight.

Let us help you with a response plan review that considers your risk of a Data Breach.

A Note of Appreciation

Thanks to Jeff Mathis and the LinkedIN Cyber Resilient Community Dialog for bringing this to my attention.

Enhance Data Breach Response – 6 Recommendations

The GAO in Congressional testimony made the recommendations

A report of the testimony is available from the GAO Web Site. For some interesting statistics from this report refer to GAO Statistics on Cyber Security.

Key Management Practices

- Establish a data breach response team;

rely on IT security staff for technical remediation;

identify an extended team that includes the information owner, the CIO,

the CISO, the privacy officer, public affairs, and legal counsel among others. - Train employees on their role;

train of employees with access to sensitive data on their responsibilities;

train the response team on their role in the incident response plan.

Key Operational Practices

- Submit reports to appropriate entities;

prepare and submit reports for internal use, to the US-CERT within 1 hour of discovery,

and to other external entities as appropriate. - Assess the impact both in breadth and in depth;

identify the nature of the data, the number of individuals, the likely potential for harm,

and the possibilities for mitigation; this assessment determines incident actions and reports. - Offer affected individuals assistance;

as appropriate and as required, help mitigate the individual’s risk

through credit monitoring for example. - Analyze the breach response; identify lessons learned.

Coordinated Response

With this information the response team makes informed decisions on what resources to apply and what actions to take. Refer to our Response Management Framework for added insight.

Let us help you with a response plan review that considers your information security risk assessment.

Harvard Business Review on Incident Response Planning

Ten Steps to Planning an Effective Cyber-Incident Response.

Tucker Baily and Josh Brandley, both with McKinsey, published an article on the HBR blog network identifying the 10 steps towards an effective incident response plan. Their article highlights some of the experiences that led to their conclusion. It’s worth a quick read.

Here I paraphrase their list to emphasize the key points and I relate these points to our response management framework.

- Assign a lead executive responsible for the plan and its implementation.

This executive is a key member of our core response team. - Develop a taxonomy of risks, threats, and potential failures

or as we like to say “align incident response to risk assessment”. - Develop quick response guides for likely scenarios.

This is our incident-action matrix – each row represents actions for a specific incident type. - Focus on major decisions, for example, when to isolate a system or part of a network; establish the procedures for these major decisions. This is a continuation of the incident-action matrix.

- Maintain relationships with external stakeholders, for example, law enforcement.

External stakeholders are part of the extended response team. - Develop relationships with external experts and service providers; include service level agreements.

These are additional members of your extended response team.

- The response plan needs to be refreshed and available.

- Ensure response team members know their role (see 10).

- Identify key response team members; insure redundancy.

- Train, practice and simulate incident response activities.

Coordinated Response

This is a good list of 10 key success factors for an effective incident response program. It serves as a good checklist against our Response Management Framework. Let us help you with a response plan review that considers your information security risk assessment.

Citation

Bailey, Tucker and Brandley, Josh, “Ten Steps to Planning an Effective Cyber-Incident Response”, Harvard Business Review Blog Network, July 1, 2013. Retrieved 03/07/2014 from: http://blogs.hbr.org/2013/07/ten-steps-to-planning-an-effect/.

A Descriptive Definition of an Incident Response Plan

This definition may not explain how to get there, but it tells you where you want to go. It provides a descriptive definition of an effective incident response plan.

An Incident Response Plan:

- is an implementation road map;

- describes the team structure and organization;

- is reviewed and approved at the right level;

- provides organizational context;

- defines reportable incidents;

- identifies key metrics; and

- defines needed resources and management support.

This makes a good list of New Year’s resolutions for improving an incident response plan and program.

Many readers may recognize this description. This description paraphrases the description of the Incident Response Plan security control (IR-8) in the NIST Publication SP 800-53. For more information on SP 800-53 refer to What Does NIST Say about Incident Response?, March 2013.

Coordinated Response

Let us help you with a response plan review that moves forward on these valuable measures.

ISACA Incident Management and Response

ISACA – The Information Systems Audit and Control Association – is a good resource for Incident Response Teams.

The ISACA Web Site offers a white paper: Incident Management and Response. This is a link to the base page with access to the white paper as well as a good set of additional resources for Incident Planning and Response.

The paper makes key points that help strengthen a response plan including:

- The importance of the link between risk planning and response planning;

- The business value of a good response plan; and

- The importance of supporting enterprise governance in the response plan.

Attacks Expose the Enterprise to a Variety of Risks and Associated Impacts

Risk planning and response planning are linked. The risks and resulting impacts occur in the following areas:

- Reputational Risks including public relations or legal issues with customers.

- Regulatory Risks including the inability to meet regulatory compliance.

- Operational Risks including the inability to deliver key business capabilities.

- Internal, Human Relations Risks including inability to process payroll or violations of employee privacy.

- Financial Risks including loss of physical assets or remediation expenses.

This is an idea that Coordinated Response embraces in The Risk Management Framework specifically in the area of Impact Assessment and Incident Prioritization.

Business Value – An Effective Response Plan Addresses Response Risk

A robust incident response program reduces the risk of response – the probability of the response itself contributing inadvertently to risk exposure. The paper stresses the characteristics of an effective program:

- Is the plan endorsed by management?

- Is the team well-trained?

- Is the team interdisciplinary? Does the team include operational, administrative, legal, HR, PR, and management?

- Does the program employ proven plans and processes for operations and execution?

- Are metrics employed for evaluating effectiveness and identifying gaps?

- Is there a charter for the team?

- Does the plan address declaration and notification procedures? A well defined communication plan?

Impact Levels

For each impact area, it is important to provide metrics or descriptions that differentiate the impact level. Low, medium, and high are not enough as impact measures. Without metrics different people assign different meanings to the terms low, medium, and high.

An Incident Response Plan Review

It’s worth stressing that the impact component of the risk assessment can and should be used during the Incident Impact Assessment. The Response Team measures adverse impact to determine the needed response.

With this information the response team makes informed decisions on what resources to apply and what actions to take. Refer to our Response Management Framework for added insight.

Let us help you with a response plan review that considers your information security risk assessment.

Insider Threats and Incident Response

Insider Threats place added requirements on an incident response plan.

In December 2012, The CERT/CC Insider Threat Center published the Common Sense Guide to Mitigating Insider Threats, 4th Edition, CMU/SEI-2012-TR-012. The guide uses extensive research to examine the nature of insider threats and their probability. It is an excellent resource.

This is the first in a series of notes on insider threats – the first note examines the guide and the next considers the impact on incident response planning and handling.

The response to insider threats often involves a wide range of organizational staff.

“Insider threats are influenced by a combination of technical, behavioral, and organizational issues” (from the Executive Summary). As a result, management,human resources (HR), legal counsel, and physical security may be involved in the response along with the Information Technology (IT) and Information Assurance (IA) departments.

Of course, this aligns with the Core and Extended Response Team in the Response Management Framework.

Insiders reflect a range of company relationships and behaviors.

The range includes:

- The traditional threat posed by current or former employees;

- Collusion with outsiders – employees recruited or coerced by competitors or organized crime;

- Business partners – suppliers, contractors, or distribution channels;

- Mergers and acquisitions introducing new, unknown insiders; and

- Cultural issues – both national and corporate – introducing tensions.

Each of these may require specialized incident actions as part of the response.

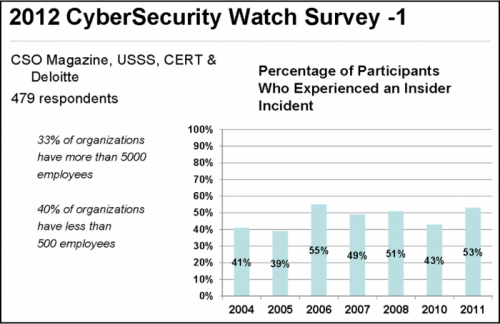

The 2011 CyberSecurity Watch Survey informs the guide.

The CyberSecurity Watch Survey provides the following statistics:

- 43% of respondents experienced a malicious, deliberate insider incident in the past 12 months.

- 23% of identified perpetrators were insiders – 1 in 4 incidents perpetrated by insiders.

- 46% of respondents felt insider incidents caused more damage than incidents perpetrated by outsiders.

This annual survey is sponsored by U.S. Secret Service, CERT Insider Threat Center, Deloitte, and CSO Magazine.

The 2012 CyberSecurity Watch Survey provides additional support.

The following chart suggests that all organizations – large and small – have close to a 50/50 chance of experiencing an insider incident in any given year. Or every 2 years give or take a month an insider incident will occur. NOTE: there were 479 respondents, 1/3 were organizations with 5,000 employees or more, 2/5 were organizations with less than 500. This suggests a representative survey.

|

||

| The 2012 Survey was retrieved from a Google search for “2012 CyberSecurity Watch”. |

The guide recommends 19 practices to mitigate insider threats.

The guide recommends 19 practices for mitigating Insider Threats (See the table at the end of this article). Many of these are well known security controls, but they are presented through the lens of the insider threat. For each practice, the guide (1) defines the protective measure; (2) identifies challenges; (3) provides case studies; (4) identifies quick wins applicable to all organizations; (5) identifies additional quick wins for large organizations; and (6) maps the recommend practices to NIST, CERT, and ISO standards.

Coordinated Response – Review your plan.

We can work with you to incorporate or improve how your response plan addresses insider incidents.

The 19 Practices for Mitigating Insider Threats.

Emphasized practices have a direct bearing on incident response planning and management.

| 1 | Include insider threats in an enterprise-wide risk assessment. | 11 | Institutionalize system change controls. |

| 2 | Clearly document and consistently enforce policies and controls. | 12 | Log, monitor, and audit insider actions with log correlation or SIEM system. |

| 3 | Incorporate insider threat security training for all employees. | 13 | Monitor and control remote access including mobile devices. |

| 4 | Beginning with the hiring process, monitor suspicious or disruptive behavior. | 14 | Develop a comprehensive employee termination procedure. |

| 5 | Anticipate and manage negative issues in the work environment. | 15 | Implement secure backup and recover processes. |

| 6 | Know your assets. | 16 | Develop a formalized insider threat program. |

| 7 | Implement strict password and account management policies and practices. | 17 | Establish a normal network behavior baseline. |

| 8 | Enforce separation of duties and least privilege. | 18 | Be especially vigilant regarding social media. |

| 9 | Define explicit security agreements for any cloud services – address access restrictions and monitoring capabilities. | 19 | Close the doors to unauthorized data exfiltration. |

| 10 | Institute access controls and monitoring on privileged users. |

From the SEI/CMU Common Sense Guide for Mitigating Insider Threats, 4th Edition.